Why is movie theater popcorn so outrageously expensive? – The Hustle

In March 2012, Justin Thompson, a 20-year-old security technician from Livonia, Michigan, decided to go to the movies.

Inside, he found an atrocity we’re all familiar with: the movie concession stand, $8 popcorn, $6 soda, $5 chocolate bars.

With no other choice, Thompson indignantly bought a gift with an 800% markup. Then he went to his house and sued AMC for charging “extremely excessive prices” on his snacks.

“They took him for a ride,” Thompson’s attorney, Kerry Korgan, told The Hustle. “sorry, but you can go and buy a bag of popcorn at any convenience store for next to nothing.”

The lawsuit was later dismissed, but it raised a question we’ve all asked ourselves: why the hell are movie theater concessions so expensive?

We set out to find an answer, and it took us right to the heart of the business model of a declining industry.

the film concessions “scheme”

Before we dive into why, let’s take a quick look at how much you’re overpaying for snacks at the movie theater.

We examined concession data from AMC, Cinemark, and other theater chains to compile rough averages of how much certain items cost. then we compare these prices to the typical street price you might pay at a convenience store.

It should be noted that movie food and drink prices vary widely based on geographic region, theater size, and a host of other factors. In the course of our research, we saw popcorn prices as low as $0.99 and as high as $13.75. The numbers you see here are rough averages and not definitive for the industry, but they still paint a bleak picture.

Moviegoers pay the highest premium for popcorn.

At most major movie theaters, a medium bag of buttered popcorn costs about $8, about the price of an average movie ticket ($9).

with 11 cups, medium movie popcorn is $0.73 per cup. By contrast, a 175-cup bag of genuine movie theater popcorn can be purchased on Amazon for $48.23, or about $0.27 per cup.

a movie ice cream ($6.49) costs 4.4 times as much as a 7-eleven slurpee (which is the same), and a soda ($5.99) costs three times as much as a coke bought at a store. with a box of m&m’s movies ($4.79) you can buy almost 3 boxes at your local walmart.

For a simple date night (say some popcorn to share, two sodas, and some red vines), you’re looking at $24.79, more than the average price of two tickets ($18). for a family of 4, the cost of snacks can run to $50 or more.

When we examine the profit margin (benefit minus cost) of these products, the numbers are even uglier.

Richard McKenzie, a professor at the University of California, Irvine, determined that it costs the average theater around $0.90 to produce a bag of popcorn. At $7.99, that’s a 788% markup.

Including the glass and a free refill, that $5.99 soda costs a movie theater $0.91 (a 558% markup); candy, which can be purchased in bulk for ~$1.16, is not far behind.

It’s easy to dismiss all of this as a simple price increase. After all, movie theaters have a captive audience, and once you’re inside, they have a monopoly on every ancillary good you choose to buy.

But the price of these concessions is not as simple as it seems.

theaters don’t earn much from tickets

Allen Michaan was just 19 years old when he built his first movie theater in the 1970s. In his 40-year career, he has operated more than 20 theaters, including the historic Grand Lake Theater in Oakland, California.

>

As he says, expensive popcorn isn’t some diabolical price gouging scheme, it’s the lifeblood of a theater’s business model.

“After the distributor takes his share, we hardly make any money from ticket sales,” he says. “We have to compensate for that somehow.”

When a theater wants to show a movie, it must agree to pay the distributor a percentage of all ticket sales. this percentage is higher during the first few weeks of a film and decreases over time, but typically averages ~70%.

so if a movie theater sells a movie ticket for $9, your cut is only $2.70, and that’s without taking into account other expenses.

Theatre owners could raise ticket prices, but it wouldn’t do them much good since 70% of any increase goes directly to the studios. instead, they think of movies as a loss leader: their main goal is to attract as many people as possible, even if it means breaking even (or losing money) on the ticket price.

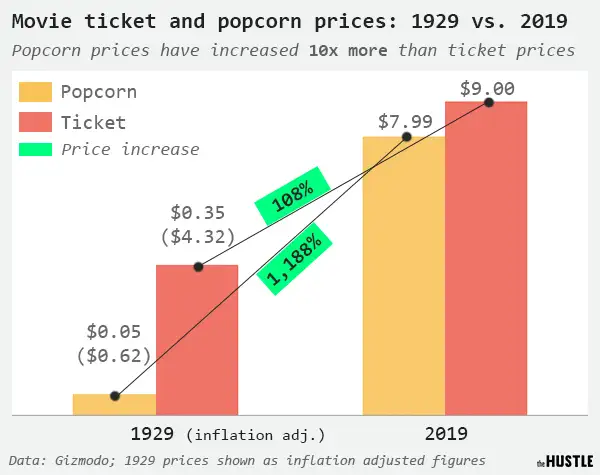

In fact, the price of a movie ticket hasn’t gone up much in the last 90 years. in 1929, a ticket cost $0.35; today, it’s $9. Adjusted for inflation, that’s a pretty reasonable price increase of 108%.

The same can’t be said for movie popcorn: Over the same period, its price has gone up a whopping 1,188% — more than 10x the increase of a movie ticket.

Movie theaters’ margins aren’t based on their core product (movie tickets), but on secondary products at the snack stand, where customers gobble down ice cream and gulp down grains of butter.

“If we didn’t charge as much for concessions as we did, movie tickets would be $20,” the CEO of Regal Cinemas, the nation’s second-largest movie theater chain, told the Los Angeles Times in 2008.

To survive, Regal and other movie theaters adhere to an old industry adage: “Find a good place to sell popcorn and build a movie theater there.”

the popcorn business

Unlike tickets, concession sales are not shared: theaters keep 100% of the revenue they generate. and these revenues generate much higher profits.

the hustle reviewed the annual reports (2015-2018) of two leading movie chains (amc and cinemark) and found that concessions account for ~30% of total gross receipts, but make up 45-50% of gross earnings.

In 2018, Cinemark sold $1.8 billion worth of tickets at a cost of $1 billion (distributor fees). By contrast, the concessions generated $1.1 billion at a cost of just $181 million, an 84% profit margin.

This strategy of selling a primary good at cost (or at a loss) and getting most of the profit from a complementary good (such as popcorn) is a form of the widely used razor and razor business model . Microsoft, for example, will sell their xbox consoles at a huge loss for people to buy them and then make a healthy profit on games and accessories.

“Theaters are able to keep a positive profit because of concession sales,” says Ricard Gil, a business professor at Queen’s University in Canada.

Gil, along with a colleague from Stanford, analyzed five years of revenue data from a major movie chain and found a different motivation for expensive popcorn: Movie theaters use it as a way to discriminate prices or charge extra. customers variable prices for the same experience (in this case, watching a movie).

“there is a wide dispersion in the willingness to pay for a cinematic experience”, says gil. “How much a customer values his cinematic experience is positively correlated with his valuation of the concession’s consumption.”

some moviegoers value the experience of seeing a movie at $9 and buy only the ticket; others might value it at $23.50 (the price of a ticket, plus popcorn and ice cream). Snacks allow a theater to segment its customer base into “high value” and “low value” groups.

popcorn does not save

Even with $8 popcorn and 84% profit margins, most movie theater owners aren’t living the high life.

“I’m not getting rich off what you pay for popcorn and soda,” says Paul Turner, who runs the Darkside Cinema in Corvallis, Oregon. “I drive a van for 26 years.”

Popcorn profits, he says, are used to pay for the high overhead costs of operating a theater: staff, rent, air conditioning, utilities, and the constant upgrades (surround sound, imax, 3d) that theaters demand. consumers.

p>

Popcorn can’t save the bones of a declining industry, either.

Less than 10% of the American population goes to the movies, compared to 65% in 1930. And those who do attend fewer: In 2018, the average moviegoer paid just 3.5 tickets, compared to 4.9 2002 entries.

As a result, the National Association of Theater Owners says the number of theaters in the United States has fallen from 7,477 to 5,869 (-22%) in the last 20 years.

Consumers have cited the high cost of tickets and concessions as a main deterrent to seeing a movie. In turn, theaters have made efforts to lower these prices, ranging from refillable popcorn buckets to annual subscription models.

but at the end of the day, some customers, like gil (the economist who examined outrageous snack prices), are still willing to pay for the experience, even if it’s 788% markups.

“I have small children, so going to the movies is almost utopian,” she says, “and when I go, I certainly buy popcorn.”