A life in feuds: how Gore Vidal gripped a nation – The Guardian

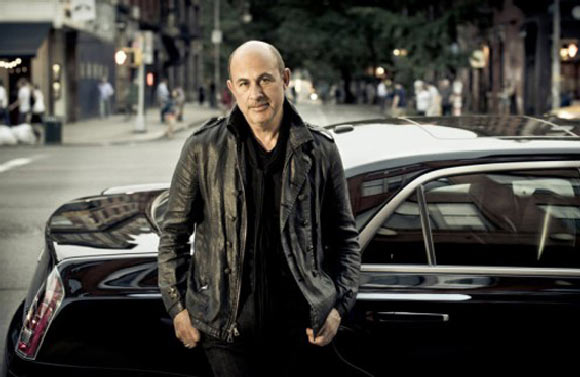

i met gore vidal in the mid 80s, when i lived in south italy, he was practically a neighbor, and our friendship lasted until his death in 2012. needless to say, he was a complicated man and, often combative. . it took an effort, strenuous at times, to remain a close friend; but I thought it was worth spending time with him, allowing him to relax into the deeper self of him, who was actually quite shy, even lonely. the public mask did not suit the private man very well, and he always felt very relieved when he took it off.

Vidal would dwell for a long time on their feuds and would focus on the idea, which he took from Goethe, that talent is formed in stillness but character is formed “in the current of the world”. he entered that stream and swam vigorously, often against the current. And his extensive knowledge of the world influenced his work: brilliant historical novels, especially Burr (about Aaron Burr, a founding father) and Julian, about the fourth-century Roman emperor. His seven novels on American history form an elegant and entertaining interlocking series that stretches from the Jeffersonian years through the mid-20th century, displaying his vast scholarship in a pleasing way. His Essays, Collected in United States: Essays 1952-1992, constitute more than 1,000 pages of vivid writing about books and ideas, perhaps his major contribution to the Republic of Letters. his perspective is always that of the high intellectual. as john lahr once said, vidal “pees from a huge height”.

A brilliant writer and public intellectual who could conquer the world when he deemed it necessary, Vidal was a courageous figure on the political scene who would stand up for the things that meant a great deal to him, and he argued his case eloquently before a wide audience. he was that almost extinct variety of human being: a famous writer whose fame stretched far beyond the realms of literature: a wit, a political pundit, a sought-after TV guest, a scold, and so much more. As he himself put it: “I am a propagandist at heart, a tremendous hater, an annoying scold, complacently positive that there is no human problem that cannot be solved if people simply do what I advise.” that he was also a brilliant novelist and essayist was often beside the point.

From the start of his career in the late 1940s, he would look around to see who else was drawing attention, and he was annoyed when others seemed to be passing him by. Truman Capote certainly annoyed him, and he honed his talents to feud with this young feline novelist from the American South whose first novel, Other Voices, Other Rooms, swept the best-seller lists in 1948. That same year, Truman Capote’s first great novel vidal, the city and the pillar, came noisily on the scene; one of the first American novels with an explicitly gay theme, it made Vidal something of an outcast in the literary establishment.

Vidal lived in new york after the war, just like capote, and they moved in the same social circle, which tennessee williams presided over. “I met Truman for the first time in Anaïs Nin’s apartment,” Vidal recalled. “My first impression, since I wasn’t wearing glasses, was that it was a colorful ottoman. when I sat on it, it squealed. he was truman.”

vidal was terribly annoyed that when life magazine published an article about the new generation of writers, it featured a large photo of capote and a small one of vidal. the two men argued endlessly in those days, trading jabs in the press over each other’s styles. Vidal accused Capote of imitating Carson McCullers’ prose with “a little Eudora Welty” for good measure. Capote suggested that Vidal’s main literary influence was the New York Daily News. Upon hearing this particular exchange, Williams rolled his eyes in mock horror: “Please! you’re making your mother sick.”

in 1948, vidal traveled to paris, where he met with williams and christopher isherwood, and, for the purpose of his visit, he saw the greatest statesman of world literature, andré gide, who had won the nobel prize for literature the year before. Gide was at the height of his fame, a public intellectual who represented, for Vidal, a kind of ideal. Like Vidal, he considered homosexuality absolutely natural, pointing out that it could be found in the most advanced cultural moments in history. That Gide was also gay intrigued Vidal, and he gratefully accepted from the 79-year-old writer an inscribed copy of Corydon, a four-dialogue volume on homosexuality.

The young writer admired Gide’s stern manner, recalling his large bald head with a dent across the forehead, skin like rice paper, and eyes that sparkled with a combination of “lust and intelligence.” Gide was smoking, speaking in Mandarin French about Oscar Wilde and Henry James as if he were giving a lecture. when vidal found out that capote had been there only a couple of days before, he nervously asked the old teacher how he had found him. “who?” Gide asked. then he remembered that there was a young American author with that name and found on his desk the article on life that appeared as a cape. as expected, the young vidal made a face.

novelist/composer paul bowles was friends with both capote and vidal, who decided to meet him in morocco in the summer of 1949. when bowles explained that capote was also planning to go, vidal invented a practical joke. he thought it would be funny if capote got out of the boat and saw bowles with vidal next to him. and the scenario developed very well. When Bowles met Capote on the dock, Capote looked back to see Vidal with his hands in his jacket pockets, as if he were his permanent resident. the cape’s face fell “like a soufflé stuck in a freezer,” recalled a French diplomat who happened to be there at the time.

Theirs was a minor dispute, and neither side missed an opportunity to make a joke about the other. But the feud grew in the 1960s, after Vidal was -according to Capote, in an interview with Playgirl- kicked out of the White House by Bobby Kennedy because he was “drunk and obnoxious.” Indeed, Kennedy had taken umbrage at Vidal’s apparent intimacy with Jacqueline Kennedy (the First Lady was distantly related to Vidal by marriage) and the writer had stormed off. vidal sued capote for the remark and capote countersued. the legal case dragged on and vidal won in the end, although capote had no money at the time, so it was a pyrrhic victory.

Their feud continued until Capote, ill from his abuse of alcohol and prescription drugs, died in the late summer of 1984. When Vidal’s editor called from New York with the news of his rival’s death, Vidal later commented a brief pause: “a wise professional decision.”

Vidal and Norman Mailer first met in a mutual friend’s Manhattan apartment in 1952. Mailer had caused quite a stir with The Naked and the Dead, his best-selling Pacific War novel, frustrating many. Vidal, whose own war novel, Williwaw, had barely registered. the two young writers surrounded each other cautiously and began a complicated friendship that would unfold over the next five decades. the two had little in common. “Norman imagined himself to be some kind of boxer, even though he really wasn’t,” says gay talese, a friend of both men. “Actually, Norman was soft. but he put on this aggressive mask. Vidal had another type of mask: fresh, soft, worldly. he was a nice contrast to norman. they played well together, but it was always some kind of performance. both understood the publicity value of this contest and let it unfold in different ways.”

The real trouble began in 1971, when Vidal decided to review Mailer’s incendiary book on the feminist movement, The Prisoner of Sex. She fired Mailer, combining him with two other males, Henry Miller and murderous Charles Manson, to create a single male bully and sexist pig she named “M3.” Vidal wrote: “women are not going to get ahead until the m3 is reformed, and that is going to take a long time.”

needless to say, mailer didn’t like being compared to the likes of manson. Never, by his own admission, one to pass up an opportunity to be on television, Vidal accepted an offer from Dick Cavett to appear on his talk show with Mailer. In the green room, according to Mailer’s account, Vidal put a warm hand on the back of his neck, a gesture that he interpreted as a veiled aggression. Mailer responded with a not-so-playful smack to the cheek. To Mailer’s surprise, Vidal slapped him back. Then Mailer leaned forward like a boxer and, in a move he suggested to Vidal that he’d been drinking, he winked at her before butting his head on the cheek.

on the show, mailer expressed his disapproval of vidal, saying he was intellectually shameless. Somewhat awkwardly, he described Vidal’s writing as “no more interesting than the stomach of an intellectual cow.” Vidal ignored him, offering him an innocent smile. But Mailer attacked again, asking her why, for once, she didn’t speak directly to him instead of speaking to the audience. He then lashed out at Vidal for alluding to the fact that Mailer had stabbed his wife in 1960, calling him a “liar and hypocrite.” Vidal did not flinch. Instead, he remained eerily calm when Mailer asked him to apologize for comparing him to Manson. “I would apologize if, if it hurt your feelings, of course I would,” Vidal said. mailer responded: “no, the sense of intellectual contamination hurts me”. Vidal smiled serenely. “Well,” he said, “I must say that as an expert you should know about such things.” The conversation became increasingly hostile, but – as anyone watching a clip of this broadcast will notice – Vidal never lost control of himself. on the other hand, mailer came out looking like a thug.

The two avoided each other for a few years, but their rivalry came to a head in 1977, when Vidal and his partner, Howard Austen, were passing through New York. “Howard loved New York,” Vidal said. “he never did. he has all the dirt and confusion of calcutta without the cultural comforts.”

One night they attended a party for Princess Margaret, before going to a large apartment owned by Lally Weymouth, a journalist and daughter of Katherine Graham, editor of the Washington Post. 100+ guests packed in. “You could barely breathe,” Austen recalled, “all standing shoulder to shoulder.” It was a dazzling event, with Mailer, Jackie Kennedy Onassis, JK Galbraith, Gay Talese, William Styron and Jerry Brown, Vidal’s future rival for a California Senate seat, among the guests.

what happened next varies by narrator, but austen’s version agrees with everyone else’s:

[mailer] saw gore surrounded by friends, all talking and laughing. gore was in a good mood when mailer approached him, he got in his face and everyone around him fell silent. seemed like a problem. Norman told Gore that he looked like an old Jew, and Gore shook his head. he didn’t want to mess with norman. then mailer threw his drink into gore’s face, right in his eyes, and then hit him in the mouth with a punch, sort of a glancing hook. Gore was stunned, and he took a step back. he wiped a trickle of blood from his mouth with a handkerchief. then gore said, “norman, once again words have failed you.”

This confrontation in the Weymouth flat became emblematic of a time when literary lions roared against each other. “It was all very tedious,” Vidal said, referring to the meeting as “the night of the little fists.” For his part, Mailer had another version, as he wrote to a friend: “I headbutted him, I threw the gin and tonic in his face and I bounced the glass off his head. it was enough to set you or me up for a half hour war, but vidal must have thought it was the second battle of stalingrad because he never made a move when i invited him down. twenty-four hours later he was telling everyone that he had pushed me across the room.”

in 1984 mailer decided to call a truce and invited vidal to participate with him in a fundraising event in new york. “our enmity, whatever its root may be for each one of us”, he wrote to vidal, “has become a luxury. it is possible that in the next few years we will both have to crew the same ship that is sinking at the same time. Other than that, I’d still like to make amends. an element in me, utterly immune to weather and tides, loves you regardless.”

Vidal said: “I never disliked Norman, not really. So now the feud, for what it was worth, was officially over. This was fine with me, as long as I didn’t have to read another one of his books.” The couple would hold several fundraising events over the past decade and the truce held.

This was never the case for William F. Buckley, who was satan as far as Vidal was concerned: a vicious right-wing debater who represented everything that was wrong with American society. Buckley was the quintessential American conservative of a certain breed: Roman Catholic, Ivy League-educated, wealthy, with a Mid-Atlantic accent that at times seemed to parody himself. He founded the National Review, a conservative magazine, in 1955 and used it as a platform to become a spokesman for laissez-faire, pro-business economics, and a tough, anti-communist foreign policy. With his first book, a spirited memoir titled God and Man at Yale (1951), he had laid down the gauntlet, helping launch the movement that ultimately led to Ronald Reagan’s presidency.

admittedly, buckley and his circle did a good job in the 1950s and early 1960s of distancing themselves from segregationist and anti-semitic voices in the US conservative movement. Buckley disliked the libertarian novelist Ayn Rand (atheist), as well as Governor George Wallace (an obvious racist, in his opinion). Like Vidal, she had denounced the John Birch Society, a far-right organization, as representing a dangerous turn in American political thought.

Vidal would never accept that he and Buckley had anything in common. But they shared similar backgrounds, with roots in the South: Vidal’s grandfather, a powerful US senator, came from Mississippi, and Buckley’s father had struck it rich as an oilman in Texas. while they took opposite stances on many aspects of foreign and domestic policy, they shared more than they would admit.

Their most infamous confrontation occurred in 1968, events now captured in the feature-length documentary The Best Enemies. A few months before that year’s presidential nominating conventions, Vidal was asked to appear in a series of 10 prime-time television debates with Buckley, moderated by Howard K. smith, one of the most respected journalists in the country. This promised to be the intellectual and political struggle of the decade, and Vidal took it very seriously. “He was like a professional boxer getting ready for the big fight,” Austen recalled. In his hotel suite, Vidal took elaborate notes on hot-button issues like the Vietnam War, housing for the poor, and constitutional rights to assemble to protest. He knew that Buckley would come well armed with statistics and Jesuit arguments, and he planned to return fire with whatever he could muster.

It’s important to remember the historical context. The Vietnam War had escalated, and President Johnson had stepped up recruitment, calling for 48,000 new soldiers, a move that inflamed America’s college-age generation, creating resistance on a scale no one in Washington could have foreseen. martin luther king, jr had been assassinated in memphis in april, bobby kennedy in los angeles in june. “We had always been a violent country,” Vidal said, “these deaths confirmed what we already knew.”

The Buckley and Vidal debates drew 10 million viewers per session, and the saturation coverage made both men celebrities. from the start, the tension between the opponents was clear. Buckley’s manner was pompous, with his tongue wagging and his eyes leering. Vidal was only slightly less pompous, with affectations and gestures that seemed, even to his friends, exaggerated and perhaps out of place.

buckley attacked vidal for spending much of the year in europe, implying that he was a traitor because he lived in rome. By the third debate, Buckley had begun mocking Vidal’s popular if scandalous sex change novel, Myra Breckinridge, which he described as pornography. Vidal responded forcefully: “If there was a contest for Mr. Breckinridge, you would win it for sure. I based his style controversially on you: passionate but irrelevant.” He referred to Buckley as “the Marie Antoinette of the right,” someone who wished to impose her own “bloodthirsty neurosis” on American politics. allusions to homosexuality were rife, with Buckley implying that Vidal was clearly “other”; vidal hinted that buckley was a closet queen.

The real fight started in Chicago, where the last debates were held. more than 10,000 protesters belonging to various student movements converged, despite the refusal of the mayor, richard daley, to allow the permits. as vidal saw it, this abrogated the “right of assembly” as established in the constitution. On August 28, the day of the seventh debate, there had been a “police riot”, as described in the subsequent Walker report. a young protester had lowered the american flag in grant park and the police pounced on him. tear gas filled the air and clubs were swung. The nation watched in horror as America seemed to descend into anarchy.

the evening’s debate featured fireworks never before seen on US prime-time television. Buckley spoke for the older generation when he denounced lawlessness in the streets. he exuded patriotism. When Smith asked her if raising a Viet Cong flag in the middle of the Vietnam War was unduly provocative, she nodded, saying it was like raising a Nazi flag in the United States during World War II. Vidal shook his head, referring over and over again to the “right of assembly.” “What are we doing in Vietnam if you can’t express yourself freely on the streets of Chicago?” he wondered.

He spoke about the repressive treatment of protesters, alluding to the riots in the streets in front of the convention center. Buckley interrupted him, recalling the time George Lincoln Rockwell, leader of the American Nazi Party, had marched with his followers to a small town in Illinois. They had been turned down, and Buckley thought this had been justified by the unusual circumstances. Taking cue, Vidal prodded Buckley: “As far as I’m concerned, the only pro- or crypto-Nazi I can think of is yourself.” It was a deadly statement, and Buckley pursed his lip and sneered, “Now listen up, fagot! Stop calling me a crypto-Nazi or I’ll punch you in the fucking face and you’ll be stuck.”

Responding to an interviewer the next day, Vidal said: “I’ve always tried to treat Buckley like the grande dame that she is.” not surprisingly, three years of lawsuits and countersuits followed, with no clear victory for either. After Buckley’s death, Vidal wrote a caustic obituary of his old enemy that ended: “rip-wfb-in hell.”

A subsequent dispute involved Christopher Hitchens, the English journalist and flamethrower who, in his early days as a left-wing polemicist, was inspired in part by Vidal. “It wants to be me,” vidal used to say, once designating hitchens, whom he affectionately called hitchy-poo or, more often, the poo, as his successor. In a witty counterattack, Hitchens printed a few words from Vidal on the cover of his memoir, Hitch-22: “I’ve been asked if I want to name a successor, an heir, a dauphin, or a dauphin. I have decided to name Christopher Hitchens.” the quote is crossed out, with a handwritten note next to it: “no. cap.”

as a young man, hitchens seemed to enjoy the role of vidal-come-lately, and he didn’t waste the opportunity to appear on television or comment on any political developments. he drank alcohol in amounts that even vidal thought were excessive. From the start, he had been suitably anti-establishment and anti-religious in ways that pleased Vidal, who spoke of him with admiration. when hitchens attacked henry kissinger or mother teresa, vidal applauded, although he told me “he will always be vidal-minor”.

later, hitchens moved to washington dc and, according to vidal, “fell among thieves.” Hitchens supporting the 2003 invasion of Iraq was, for Vidal, off limits. Vidal had written several best-selling pamphlets against George W. Bush and his gang in the years after 9/11, and had become vividly relevant in later life as a defiant critic of the White House and its brutal warmongering. Quite rightly, he predicted that the overthrow of Saddam Hussein would lead to chaos in the Middle East.

“He’s gone crazy, our poo,” he told me one winter afternoon in 2010, after Hitchens published a nasty article about him in Vanity Fair called “Loco Vidal.” Hichens criticized Vidal’s three post-9/11 pamphlets, calling them “half-argued, half-written punch pieces.” He also attacked him for giving an interview in which he criticized George Bush and Dick Cheney, saying that “the whole American experiment can now be considered a failure.” hitchens seemed particularly irritated when vidal said of britain: “this is not a country, this is an american aircraft carrier”.

on october 2, 2010, shortly after hitchens was diagnosed with esophageal cancer, i spoke with him at a book festival in pennsylvania. I was already brittle. we sat together in his hotel room and talked, and as i was leaving he asked me if vidal had talked about him recently. I couldn’t tell him the truth. “I wasn’t happy about your vanity fair article about him,” I said, “but he still thinks of you fondly.” Hitchens smiled and said: “I saw him as a model. we all did.”

sex, appearance and lawsuits – gore vidal in quotes

Class is the most difficult subject for American writers to deal with and the most difficult for English writers to avoid.”

a narcissist is someone prettier than you.”

Half of Americans have never read a newspaper. half never voted for president. one expects it to be the same half.”

In reality, there is no such thing as a homosexual person, just as there is no such thing as a heterosexual person. words are adjectives that describe acts, not people.”

luckily for the busy lunatics who rule us, we are permanently the united states of amnesia.”

American writers don’t want to be good, they want to be great, and neither are we.”

after a certain age, fighting takes the place of sex.”

I’m all for bringing back the birch, but only between consenting adults.”

America was founded by the brightest people in the country, and we haven’t seen them since.”

never miss an opportunity to have sex or be on television.”

we should stop babbling that we are the largest democracy in the world, when we are not even a democracy. we are a kind of militarized republic.”

the four most beautiful words in our common language: I told you so.”